Abkhazia’s abortion ban is back in the news after a woman spoke out about a relative being forced to carry her pregnancy to term in spite of medical complications.

Earlier in October, Victoria Gularya posted on Facebook the story of a relative who was being forced to take her pregnancy to term. Despite doctors telling her relative that the baby would certainly die, she was unable to get an abortion.

Saria (not her real name), a gynaecologist and ultrasound diagnostician, told OC Media that ‘there is simply no chance for such a child’.

‘And we are forcing this girl to carry him’, she added.

Abortions in Abkhazia were outlawed in December 2015 in an effort to boost birth rates, marking a major blow to women’s rights. The only exception is in cases of antenatal fetal death.

The amendment banning abortion was initiated by MP Said Kharazia, who based his initiative on religious considerations and the fact that this was the way to improve the demographic situation in Abkhazia.

‘Everything that breathes must be born’, Kharazia said in response to outraged appeals from Abkhazians asking for the law to be amended to at least allow abortions for medical reasons.

The amendment to the second chapter of the Constitution says that ‘the state equally protects the life of the mother and the unborn child’.

In February 2016 an amendment signed by then-President Raul Khajimba was also made to the Law on Health Care, in which Article 40, ‘Encouraging Motherhood’, states that ‘the state recognises the right to life of an unborn child from the moment of conception and prohibits artificial termination of pregnancy’.

It remains unclear what the sanctions for illegally obtaining an abortion are. However, a source in the General Prosecutor’s Office told OC Media a woman who terminated her pregnancy would face 3–7 years in prison under Article 105 of the Criminal Code — Intentional infliction of grievous bodily harm — and that it could even be qualified as murder.

The source said that that a doctor performing the abortion would stand trial on Article 116 of the Criminal Code — illegal abortion — which is punishable by a fine of ₽10,000–₽25,000 ($140–$350) or community service for up to two years.

‘I don’t understand how MPs live with themselves’

Valeria, a 31-year-old mother of two, is one of many women in Abkhazia deprived of the right to an abortion.

Her eldest was born with Down’s syndrome. While her youngest child is healthy, during pregnancy, Valeria made several expensive genetic tests which showed there was a high risk of the child having chromosomal abnormalities.

Six months ago, she fell pregnant again. The first screening showed again a high risk of Down’s syndrome, but she was refused an abortion.

Most women deciding to terminate their pregnancy end up going to Russia. Since Valeria does not have an Abkhazian passport, she had to organise everything through a doctor in Sukhum (Sukhumi).

‘My gynaecologist called her classmate who works in Sochi, and she received me. She examined me, asked for tests, did an ultrasound scan, and gave me two pills, which I had to take at intervals of 12 hours. She explained everything that would happen to me’, says Valeria.

‘There were no complications. I paid the Sochi doctor ₽13,500 ($190) and put ₽5,000 ($70) into the pocket of the doctor in Sukhum, even though she did not ask for it. But it was necessary to thank her’.

Valeria says she does not regret that she terminated her pregnancy.

‘I know what it is like to raise a sick child, how much nerves, energy, and money it takes. For eight years in a row, I have cried every day looking at my daughter, who will never be a fully functional member of society.’

‘I either regret giving birth to her, then I scold myself for these thoughts. But I know for sure that I will not wish such a fate on the enemy, but our MPs do. I just don’t understand how they live with themselves after they voted for this inhuman law’, Valeria says.

Futile efforts of activists

Victoria Gularya, who told the story of her relative on social media, ended up deleting her post.

As Abkhazian Human Rights Commissioner Asida Shakryl said during a press conference on 7 October, she had to do so after being threatened.

Shakryl did not name the person from whom the threat emanated, but hinted that it was a reputable official and urged the government to pay attention to such incidents.

She also spoke about the death of a woman who went to Russia for an abortion. According to Shakryl, due to complications caused by the operation, the patient died on her way back to Abkhazia.

One doctor in Sochi who provides abortions to patients from Abkhazia told OC Media that the vast majority of cases were medically justified terminations of pregnancy.

From the moment the abortion ban was introduced, the Association of Women of Abkhazia began to fight against it. The association’s chair, Natella Akaba, has spoken publicly more than once calling the law discriminatory against women.

The association previously appealed to parliament and to then-president Raul Khadzhimba on multiple occasions, but their appeals have received no attention from either the legislative or executive authorities.

Akaba says that in many ways, the problem stems from the fact that a decision on abortion was made mainly by men — a point that highlights the lack of gender balance in Abkhazian politics.

She says that men had decided to raise the birth rate, and had done so ‘like men’.

‘Over the past five years, there have been no significant changes, and the demographic situation […] has virtually not changed’, says Akaba. ‘Women continue to terminate unwanted or dangerous pregnancies by travelling to neighbouring countries or performing illegal abortions in Abkhazia.’

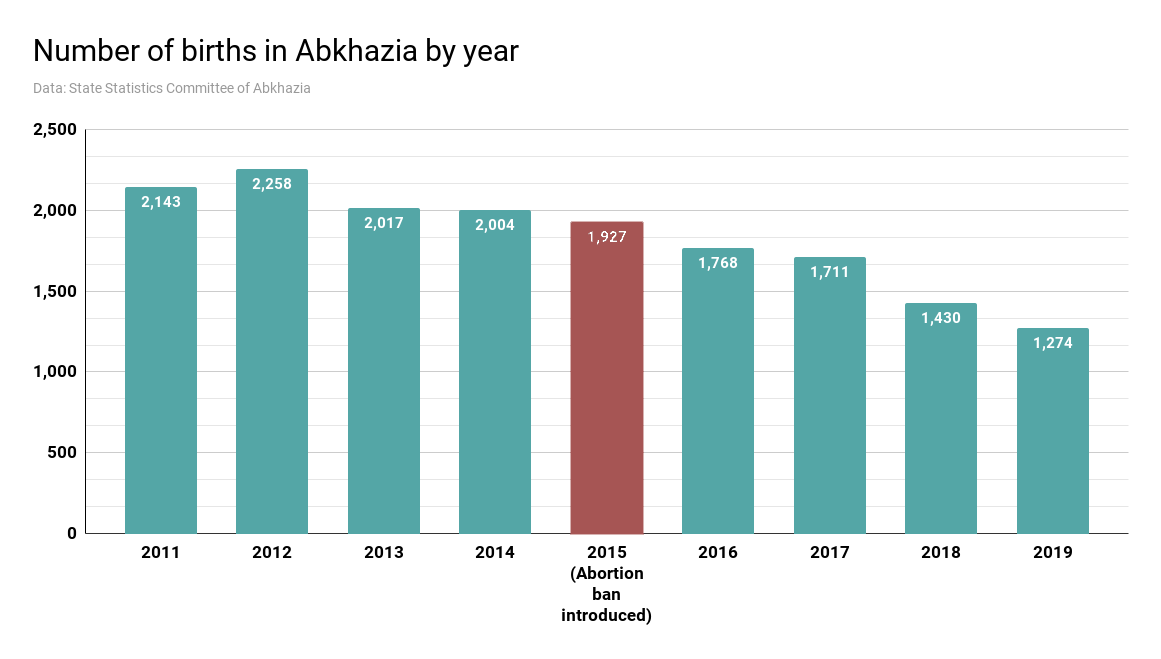

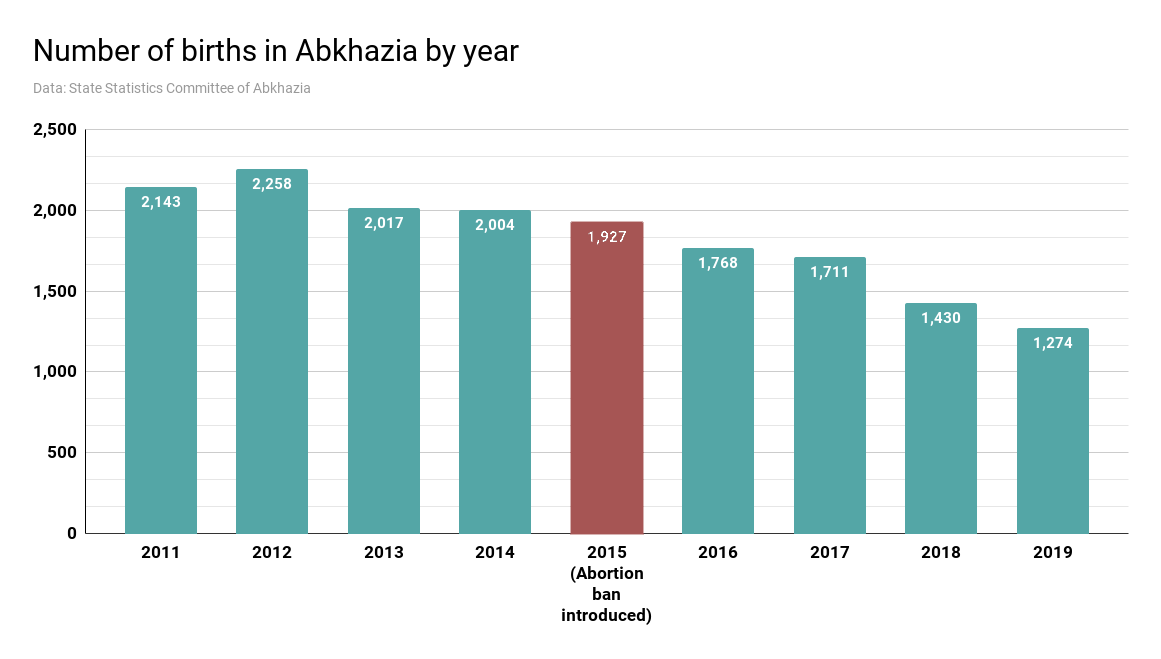

As activists said at the time the ban was introduced, it has not led to an increase in the birth rates — which are still steadily declining.

According to statistics from Abkhazia’s State Statistics Committee, in 2014 there were 2,004 births, which fell to 1,768 in 2016, the year after the ban was introduced. In the following four years, the trend continued with an average of only 1,545 births per year — and only 1,274 in 2019, the latest year on record.

‘As international experiences show, banning abortion does not help to increase the birth rate’, she says. ‘With [an introduction of] such bans, the number of illegal abortions increases, which can have a detrimental impact on women’s health’.

The primary geographic terms used in this article are those of the author’s. For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.