Robots ferry containers of Nike shirts across the factory floor while plasma screen televisions drive workers to labour ever faster. In the third and final part of OC Media’s exposé on Georgia’s textile industry, investigative journalist Tamuna Chkareuli infiltrates a high-tech factory in Poti.

[In this multi-part series, OC Media went inside Georgia’s factories for a first-hand account of the working conditions. Read Part I and Part II]

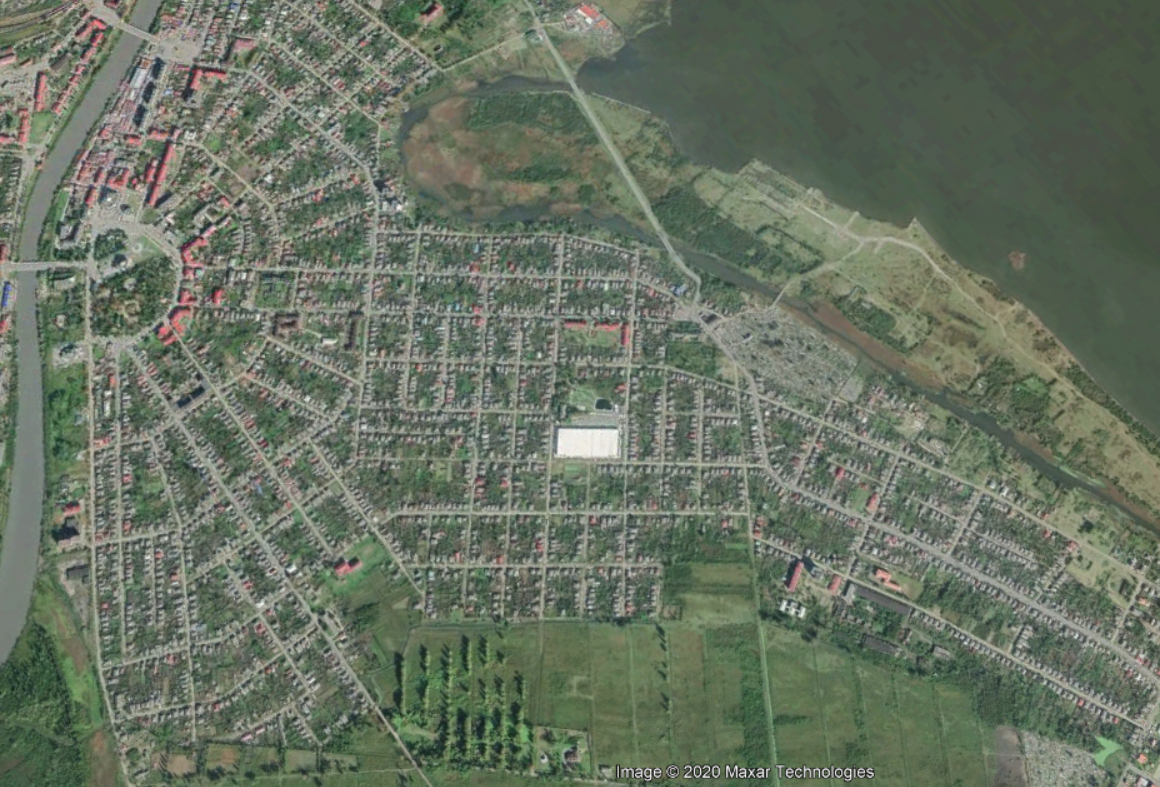

Imagine you’re a woman in her forties from the industrial port city of Poti, Georgia. Your husband probably works at the port, perhaps in customs or in shipping. You have two children who are at university or in school.

You have debts and your husband’s salary is not enough to cover everything, so you are constantly trying to save money. You don’t go out — not that there is someplace to go, even if you wanted to. You don’t take any holidays.

Your only entertainment consists of talking to relatives on the phone and visiting the neighbours. You haven’t been to a doctor in years, despite that nagging pain in your chest. You prefer to save on anything and everything because the children need an education. Maybe they can get out of this dead-end town, where there is no perspective for them.

Or maybe you are younger, one of those young women whose parents did not have the opportunity to send you to Tbilisi or Batumi to get an education, so now you’re stuck in Poti.

The only job a woman like you can get is in hospitality or maybe at the bank. But these jobs are underpaid, and anyway, you don’t speak English so they would never hire you. Most of your friends have left town or got married, and so you are desperate to change something, anything in your life.

Or you live in one of those villages near Poti that have no workplaces at all.

Or you’re a pensioner who’s struggling to find an income not to be a burden to the family.

It doesn’t matter who you are, so long as you lack opportunity and are willing to work. You start to think about going to Turkey for seasonal work, but then you hear about it — ‘the big factory’.

Maybe it was a friend, or maybe a neighbour who told you about this place and said that it is taking everyone, literally. No experience needed.

You are amazed. Can this be real?

You build up the courage to go there and ask for a job. The moment you walk in, you are struck by the magnitude of the place. How big, how clean, how organised it is. But even more, you are amazed at the conditions you are being offered — free transportation, free food, and a salary that ‘entirely depends’ — as the factory representative tells you, ‘on your desire to work’.

Breathless with excitement, you agree.

They bring in a bunch of papers and quickly tell you what to sign and where. Then human resources give you a sheet of paper with big block text that reads: ‘I have read, understood, and am confirming’. You need to copy these words right here, they tell you. The salary is a bit low, but it’s definitely better than what you have now. You write down the words and then sign.

This did not happen to me. Not exactly like this. But this, or some variation of this, happened to my co-workers who told me their stories. And when I applied to work at the Poti branch of Ajara Textile, I pretended that I too was one such woman.

Ajara Textile

Ajara Textile is a subsidiary of Turkey-based Abay Uluslararasi Tekstil Turizm ve Yatirim (Abay International Textile Tourism and Investment) which is, itself, a subsidiary of Aceka holding, a large Turkish company that has been operating in the textile industry for over 60 years.

Ajara textile has three branches in Georgia, one in Poti, one in Batumi, and one in Bobokvati. It employs roughly 3,000 people.

The Poti branch was supported by a ₾9.2 million ($3.3 million) loan from the Georgian government through the Produce in Georgia programme (also known as Enterprise Georgia). It has produced t-shirts for the Polish and Croatian teams competing in the FIFA World Cup in 2018, as well as for the Italian team competing in 2012.

The Poti municipal assembly told OC Media that before the opening of the factory in late 2017, company representatives had several consultations with then-assembly chair Aleksandre Topuria, who has since left the public service.

Topuria denied having consultations with the company, stating that his only interest was to ‘create more jobs’ in the region and his involvement did not go beyond ‘offering the Turkish directors to open a branch here [in Poti] through an acquaintance’.

After resigning, Aleksandre Topuria became the general director of another Turkish co-owned textile factory in Poti.

Getting inside

To get inside the factory on a typical day, a worker must pass through gates flanked on each side by high walls topped with barbed wire, usually, they are driven in on a minibus supplied by the company.

Within the walls, the factory is surrounded by guards, mostly serious-looking men in grey coveralls. Inside, the guards, while no less numerous, are all women, in case a worker is acting suspicious enough for a pat-down search.

Under the watchful eye of the guards, workers walk in through the main entrance, which is equipped with a small fingerprint scanner. The scanner ensures that only factory workers get in or out through the main entrance, it also works as a biometric punch clock, tracking late arrivals and absences.

Past the fingerprint scanner is the locker room. That’s where you change into your uniform, usually blue or orange coveralls, and deposit your phone in a locker — lest you think of taking photos of trade secrets.

After the locker room, you have to walk through the metal detector, and if it goes off, you are carefully searched. Espionage is taken very seriously at Ajara Textile.

Unlike Geo-M-Tex, the previous factory I infiltrated, the Ajara Textile factory was hyper-clean, orderly, and high-tech. The factory building itself is a single floor, a warehouse large enough to fit several Boeing 747s.

[Read more on OC Media: Inside Georgia’s textile industry: Part II — Undercover]

The building is subdivided into several large sections, each designated for a particular stage of production (sewing, cutting, etc.). In any given section there are rows upon rows of tables where workers sit in front of machinery, each of which performs one specific task at a rapid pace (for example, applying the bottom stitch to a shirt).

In between the tables and down the halls, large markings are painted on the ground. These are for the many robots that constantly patrol the factory. From what I could ascertain, they scan the markings to orient themselves.

The robots serve the function of efficiently moving large quantities of in-production clothing throughout the factory, ensuring that raw fabric is turned into a t-shirt at a quick and regular tempo.

The workers seem fearful of the robots, and not simply because the robots move along with little regard for whoever might be in their way. Rather, the robots, when they take the containers of products from the desks of the workers, do not ask if the worker needs a little more time to fill it, nor do they respond to pleas of ‘just give me one moment more!’. They operate with a cold mechanical efficiency in the service of a production quota.

If a worker turns their eyes up, they can see plasma televisions hanging above the factory floor. With constantly changing numbers they too serve the quota, reporting what percentage of it the workers have completed at any given moment — driving them to maintain or increase the pace.

The leftovers

‘It’s not too bad here’, I said to Inga, the woman who was in charge of my apprenticeship at the factory. My voice was still trembling from all the security I had to pass before entering.

‘Let’s talk in a month’, Inga replied. She has worked in the factory for one-and-a-half years, and as there was nothing better, so she got used to it, she said.

Inga started as an apprentice just like me.

She escorted me through the factory to the place where I would receive my training: the largest and quietest of the factory’s production sections. I quickly began to think of those who worked there as ‘the leftovers’.

Ajara Textile, like many factories in former communist countries, organises its workers into ‘brigades’, groups of workers who form production teams. When a brigade becomes very efficient, it often gets dismantled so its workers can join other brigades and speed them up.

While it may be a good strategy to speed up the overall production, some workers do not get reassigned to new brigades. These workers are the ‘leftovers’. They work on small tasks, like sewing on labels, or fixing minor mistakes. While the leftover condition is temporary, as eventually brigades will be formed of the leftovers themselves, it is still undesirable, as leftover workers do not receive the salary bonuses that those in brigades do.

Apprentices like myself worked side by side with the leftovers. We too would be part of the brigades assembled out of the leftovers.

The plans for these new brigades are always ready before all the necessary workers are in place, the requisite slots simply need to be filled. And so from the moment I started training, they put me on the same machine that I would work on as part of a future brigade.

From the moment I walked into the leftovers room, I realised that at Ajara Textile, everything and everyone has their place.

Discipline and punishment

On the second day, all the new employees, including myself, were called out to the meeting room. There we were trained by Achi Martalishvili, an energetic young man from human resources who addressed us in a soft, kind tone and called us his ‘dear friends’.

He taught us about our contracts and about the company’s internal rules and regulations.

The contract at Ajara Textile stipulates a base pay of ₾300 ($100) per month, for 45 hours of work per week. A sum that amounts to ₾1.33 ($0.47) per hour. Workers get a 50% higher wage for any overtime hours and double the hourly wage if they work on weekends or holidays. Rates that, according to the company, were determined by looking at ‘the payroll data and wages of those employed in the field in Georgia’.

‘After a month of work’, Martalishvili told us, ‘you’ll be moved to the bonus system’.

The bonus system exists both at the level of the individual and the level of the brigade.

At the individual level, there are three separate bonuses: a discipline bonus that can net you an extra ₾20 ($7.20) per month; a ‘stars’ bonus for passing examinations on new equipment which is worth another ₾20; and a perfect attendance bonus worth ₾10 ($3.60).

Martalishvili described the system in glowing terms. ‘You can receive an extra ₾50 ($18) in total by doing practically nothing’, he said.

However, this seemingly effortless money-making opportunity also doubles as a method of discipline and punishment. Each of the three separate bonuses also come attached with a series of violations, that reduce their value. For example, an imperfect performance in the equipment examinations lowers the stars bonus, while missing workdays lowers the attendance bonus.

The discipline bonus is the most complicated, with a long list of infractions that lower the payout. Each is usually worth -₾2 (-$0.70). These infractions range from the very specific to the incredibly general, including eating or drinking at the workplace, talking to a colleague while working, not doing what you are told, and turning a blind eye to a mistake.

Worse still, the list of infractions is mentioned for only the briefest of moments during training. You must try to memorise it — a nearly impossible task. As a result, as you work you police yourself excessively, trying not to break any of the real or perhaps just imagined rules. It is mentally exhausting.

Compared to all this, the brigade bonus is relatively simple.

For any given item, a quota of a certain number of items for a particular period of time is established. When a brigade completes 60% of the quota, all of its members immediately receive a ₾10 ($3.60) bonus, when they complete 100% of the quota, the bonus is upped to ₾50 ($18).

The brigade bonus is limited by quality control, which is different for each brand. When we worked on Nike t-shirts, for example, 30 items were chosen at random from each brigade and if they were considered to be below standard the whole batch would be sent back. Each batch returned decreases the brigade bonus.

For some workers, bonuses are a very significant portion of their monthly paycheque.

At the end of his speech, Achi Martalishvili told us that at Ajara Textile, they were proud of their ‘no-fines’ policy. Then we proceeded to the evaluation tests.

We took two tests, one on the payments and one on health and safety hazards. We aced the tests. How do I know? Martalishvili gave us the answers. Maybe he just wanted to get it over with?

One of the hazards mentioned in the health and safety test was the danger of developing back injuries during work. It was suggested we sometimes stand up and do a three-four minute exercise during our workday to remedy the problem. After I began working, I noticed that no one did such exercises.

None of the workers, it seems, was ready to lose their brigade productivity bonus because of something as trivial as their physical well-being.

Just do it

For nine hours a day, I was learning how to quickly set thread into the sewing machine and sew straight lines that would, in short order, be the hem of Nike’s Dri-FIT t-shirts, the same ones that the workers next to me were tagging and packing in plastic to ship to Europe.

T-shirts that didn’t pass the quality control were labelled ‘tamir’, or ‘fix’ in Turkish.

I later found out that not all the stock labelled ‘tamir’ was sent back to be fixed. Instead, some of it was later sold to the factory workers themselves.

One of my colleagues described the process to me. Boxes with clothing labelled ‘tamir’ are placed outside, behind the factory, and workers are given the chance to buy them at prices below retail cost.

She strongly advised me not to participate in this ‘madness’.

‘They are really killing each other for those shirts’, she said.

Madness or no, for the company, it seemed to be a brilliant system. They got to profit on flawed stock twice: the first time, when they subtracted money from the workers for producing substandard goods, and the second time, when they sold these same goods back to them.

After my time at Ajara Textile, I reached out to the company for their comment on the practice.

‘Employees can, once in a while, purchase the clothing produced by the apprentices in the learning period for a symbolic price’, they wrote. ‘By which the company encourages and supports their employees.’

Working at Ajara Textile was not easy, all the operations require accuracy and a good eye; even the way you hold the material matters — but the workers were up to the task, I was truly impressed with how quickly and accurately they worked.

But despite the workers’ skill, speed always seemed to remain an issue. Cutting through the noise of hundreds of sewing machines and the extraordinarily loud music (which according to the employers, was requested by the workers themselves), I could always hear the repeated shouts of the brigade supervisors demanding their subordinates work faster.

Every once in a while, loudspeakers would echo the names and surnames of women who needed to ‘immediately show up at the factory administration’. You never knew the reason. It could be for punishment because of a discipline violation or perhaps for praise or even a promotion. But no one ever knew, not even the ones being called.

We had three breaks, 10 minutes in the morning and late afternoon, and 45 minutes at lunch, all announced by the ringing of a bell.

For our lunch break, we all rushed to the canteen where we were served a bit of soup with potatoes, some cucumber slices, and half a loaf of bread on metal plates. After eating, the workers would take a little time to relax, though they remained on factory premises, which include a small park and a little duck pond.

During the shorter breaks, women either chat with their neighbours or talk on the phone, as these are the only times they can do so. No one seems too happy, but they’ve come to terms with the work. It’s better, after all, than much of the other factory work available in the country, especially when one considers the lack of opportunities in Poti.

‘It was so hard at first’, said a young woman working next to me. ‘But I’m used to it now’.

She even encouraged me, telling me that when I joined a brigade, I would earn more. She said that even though the tempo of work would be faster, it was worth it. She was a leftover, and like all the other leftovers, dreamed of being part of a brigade again.

The closing bell rang at 19:00. Before we left the factory, the other workers and I gathered near the factory exits where security guards searched our bags. It took quite a while since they had to search over 1,000 people.

After we were allowed to leave the factory, most of the women headed to the waiting minibuses which took them straight home. Other than me, very few women preferred to walk.

Fear Factor

In early 2018, a young worker, Sopio Gogoladze, left her job at Ajara textile after a conflict with the management. She was five minutes late to her station after a break because she went to the restroom.

When she returned to the assembly line, she received humiliating treatment from her brigade supervisor. She complained to human resources, but Achi Martalishvili told her she didn’t have the right to use the restroom without permission.

‘He literally said that the [brigade supervisor] had the right to behave that way if I was slowing down production’, Sopio told me. ‘He spoke with such arrogance that I decided to resign. I couldn’t take this kind of treatment’.

Sopio promised Achi that she would return, this time with trade union officials and journalists in tow. The young HR manager responded that she would never find a job with better working conditions than in Ajara textile.

Sopio tried to make good on her threat and got in touch with Giorgi Diasamidze, a union leader with the Georgian Trade Union Confederation (GTUC). He advised her to gather several like-minded colleagues and to begin organising and fighting as a collective.

‘Unfortunately, they were too scared. Only one person came to the GTUC meeting — a cleaner who has also had problems’, Sopio said. ‘At one point, Ajara TV was interested in recording three of the workers, who agreed on the conditions they would be filmed from behind, but on the day of the recording, none of them showed up.’

In Poti, where almost everyone knows everyone, people generally refrain from complaining, as it might affect their future.

‘Fear is the key factor’, Sopio concluded.

After her resignation, Achi Martalishvili told a journalist from Fortuna Plus that Sopio had ‘psychological issues’. Her former classmate, who was a security guard at Ajara Textile, kindly advised her to stop talking and said that the company was willing to rehire her.

‘He told me that he could speak to the head of security and they would put me in the brigade and position of my choice, and “figure it out” with the people who offended me — if I just stop talking.’

She refused.

After her attempts to fight back against the company failed, the workers in Sopio’s brigade got a single time monthly bonus of ₾40 ($14). To this day she is the only Ajara Textile employee who has ever shared her experience publicly.

‘I know it’s Georgia and we have to close our eyes to certain things, but I was not treated like a human being there’, she said.

As good as it gets

While writing this three-part investigation, I worked inside several Georgian textile factories and heard stories of conditions inside many more. For me, there is no question, Ajara Textile is as good as it gets. While most textile factories in Georgia seem like 19th-century workhouses, working at Ajara Textile was like visiting the future.

And yet, to me, it seemed a deeply dystopian future.

My co-workers at Ajara Textile seemed miserable at their jobs. The constant stress of making the quota, the rules against speaking to each other even as we sat side-by-side for hours. Every action being constantly monitored and measured: even something as personal as a fingerprint becoming a routine part of the production process.

It felt like we were just sewing machines in the shape of people.

I don’t think my co-workers wanted to be there. But they had no choice. To feed their families, to rent a flat, to help take care of their elderly parents, to get a decent university education, or to save enough to have a shot at a decent future outside of Poti, they had to go to the factory.

And even when workers agree to a contract, there are still internal regulations to consider.

‘Violating any point of the internal regulations is the same as breaking the contract’, Lela Gvishiani, an analyst at the Human Rights Education and Monitoring Centre (EMC), who I spoke to after my time at Ajara Textile told me. ‘Very often employees don’t have the possibility to thoroughly go through such a huge document and announce their own conditions.’

‘Instead of being equal’, she added, ‘the employee is already weakened before even signing the document.’

In principle, she said, the employee and the employer should be equal but ‘there is no voice of the employee in the [Ajara Textile] contract’.

This is, of course, not unique to Ajara Textile. Far from it.

The wider legislative structure in Georgia is also geared towards privileging employers, Gvishiani said. Indeed, Georgia has even been criticised by Human Rights Watch for its ‘lax labour regulations’. For example, Georgia has a minimum wage of $7 a month, largely symbolic overtime legislation (no monetary amount for extra hours worked is specified), and a labour inspection agency that, at present, employs 40 inspectors for all of Georgia — though, they plan to increase the number to 100 this year. In the entirety of 2019, labour inspectors only visited two textile factories.

‘The investor doesn’t have any responsibilities to [Produce in Georgia], and we don’t give directives’, Nina Kakulia, investor relations manager at Produce in Georgia, the Georgian government’s programme to promote international investment in the country, told me.

Their only goal, she said, is to serve the investor to maintain an ‘investment-friendly atmosphere’ in the country.

‘We don’t perform monitoring’, she added. ‘We keep communication open [with the investor] because it’s generally very important how the investor feels in the country after starting the business and that they know that the government is eager to help them.’

According to Lela Gvishiani, this attitude is par for the course. ‘No one ever checks and asks employers for anything’, she said. ‘They are dominant, and given the job situation in the country, merely having one is already a luxury. Employers make their own rules here.’

‘Employees are left at the mercy of employers.’

This was the third part of a multi-part investigation into Georgia’s textile industry. It was prepared with support from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Regional Office in the South Caucasus. All opinions expressed are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of FES.