In Georgia, the social stigmas around disabilities combine with patriarchal attitudes in destructive ways. Ignorance, compounded by a lack of support services to help women with disabilities live independently means many women can only dream of having a private life.

Women with disabilities should be free from violence, discrimination, abuse, and harassment.

They have the right to decide where, and with whom to live.

They shall be free from any interference and surveillance in their correspondence, living space, and personal belongings, even in an institution.

Their reputation shall be respected, while personal, medical, and rehabilitation-related information shall be kept confidential.

Women with disabilities have the right to retain fertility from childhood, which means a prohibition of forced or uninformed abortion, sterilisation, contraception, or use of sexuality suppression medications.

States shall take a positive obligation to assist women with disabilities in parenting.

These are all obligations that Georgia has undertaken under the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. This does not only imply that the government is obligated not to violate these rights or protect people from violations by others — but to proactively create the necessary programmes and services for women to fulfil these rights.

While these obligations look great on paper, what’s more important is that all the ratifications, endorsements, and submissions of state reports that Georgia has undertaken positively impact and affect the everyday lives of ordinary women with disabilities.

And the truth is, for many women with disabilities, realising their right to a private life remains all but impossible.

The right to date

Women with disabilities living in the community face challenges inside and outside their homes.

Interviews with them suggest that they are deprived of the right to create a family due to a lack of support services, a lack of physical and financial independence, stigma, stereotyping and discrimination, as well as patriarchal attitudes in their families and in society at large.

Many women with disabilities point out that due to their dependency on their families, they are unable to meet and date potential partners or have healthy sexual relationships, never mind think about marriage. Family members often do not allow women and girls with disabilities to even go outdoors — afraid of sexual abuse or even of a consensual relationship emerging.

This can be motivated by a fear of pregnancy, which families may not want due to their own difficult socioeconomic situations and the necessity to assist with the upbringing of a new child. There is also a widespread fear of having another family member with a disability.

The fear of even consensual relationships can stem from the possibility for women with disabilities to be deceived or ‘used’, but also from religious taboos on sexual relationships outside marriage and the view of a woman as family property that must be protected from being taken by others unless the family approves.

While women without disabilities have the possibility of rebelling against such patriarchal views and achieving their independence, this task is far more challenging for women with disabilities, who in the absence of proper support services, are much more dependent on their families in every aspect of their lives.

One expert, for example, recalled a case of a father chaining his adult daughter to a bed for a month to prevent her from being near any men.

Medication is also used to suppress sexual desires among women with disabilities without their knowledge or consent.

The power imbalance created by disabilities and the lack of support services which could alleviate such an imbalance empower these old patriarchal views, allowing almost complete control over women.

Stigmas and ignorance

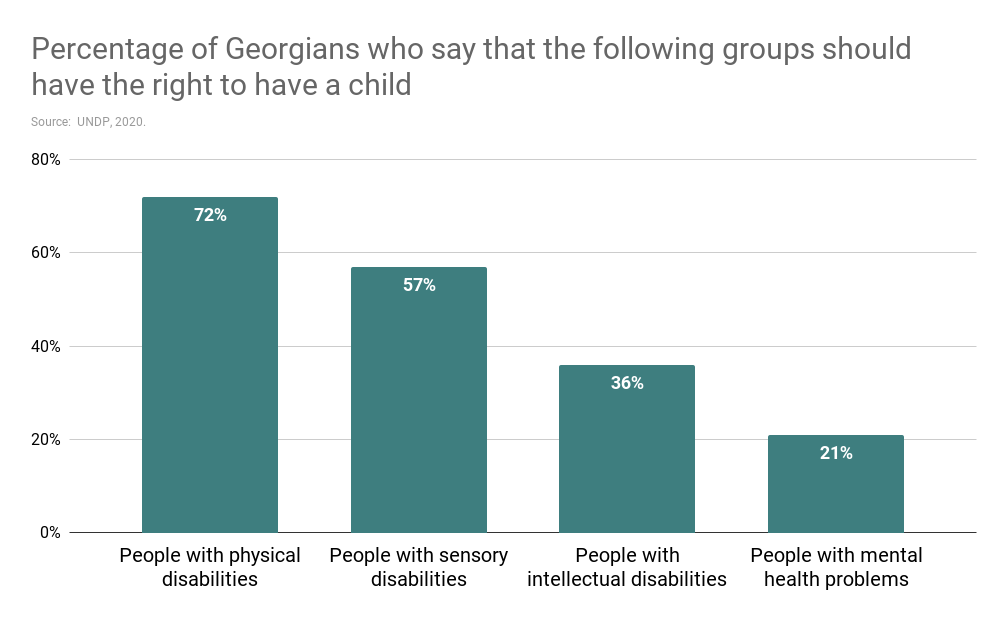

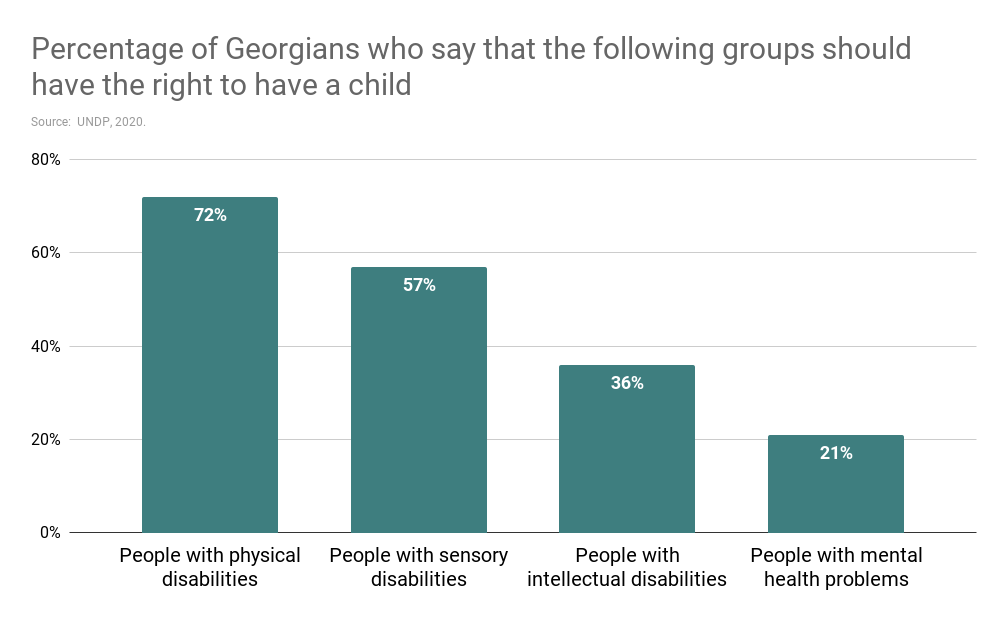

Stigma plays a significant role in shaping the behaviour of families of people with disabilities and society at large. According to a 2020 report by the UN Development Programme, more than half of the population thinks that people with intellectual disabilities or psychosocial problems should not have the right to have children; the report found a significant percentage thinks the same of people with physical and sensory disabilities.

Such stigma also leads to another big problem: ignorance. Women with disabilities lack basic knowledge about their sexual and reproductive health and rights. This is first and foremost due to the taboos and negative societal attitudes toward discussing sexuality, especially female sexuality.

However, there is also a lack of information in accessible formats for people with sensory disabilities, such as people who are blind or deaf, and people with intellectual disabilities. There is also a lack of information sensitive to the specific needs of, for instance, people with physical disabilities.

Most of the women with disabilities interviewed as part of a 2020 survey by Hera #21 said they had not received any sexual education at school. They were also often unable to discuss their sexual and reproductive health with doctors, who do not follow confidentiality standards.

It is a widespread practice for health professionals not to ask people accompanying those with disabilities to leave the room during consultations or even while performing medical checks.

Moreover, health-related information, such as diagnoses, medication prescriptions, the need for further checkups or laboratory testing, is mostly communicated to the accompanying person or in their presence, not to a patient with a disability directly.

‘Doctors would not talk to me about the health of my children. They would prefer speaking with my husband’, one mother with blindness said publicly.

Non-existent privacy in institutions

For women with disabilities living in specialised residential facilities or psychiatric hospitals, the situation can still be worse.

People who are bed-ridden are often deprived of any privacy or personal space. For example, according to standards, the spacing between beds at psychiatric hospitals should be no less than 1 metre. In reality, in many hospitals in Georgia, it is only a few centimetres. There are no screens, or walls between beds, so people lie in full view of each other.

The doors in psychiatric facilities cannot be locked, including doors to bathrooms and toilets, meaning it is possible for anyone to enter these spaces while they are in use. This can be especially stressful for women in mixed-gender facilities.

On the other extreme, in some institutions, men and women are prohibited from speaking to each other at all. They are even given separate walking spaces in the yards to prevent any communication between the sexes.

Ridiculously, this happens for long-stay patients and people in ‘social departments’ or shelters housing mostly over 50s, making fear of pregnancy unrealistic. These institutions apparently want to avoid any possibility of sexual abuse, but at the cost of complete separation, including the prohibition of even verbal communication between men and women.

In many cases, these men and women will likely remain institutionalised for life, meaning they will never have any possibility of communicating with the opposite sex.

Multi-tiered discrimination

What is described above shows that the international human rights obligations taken by Georgia are far from being met.

Women with disabilities face multi-tiered discrimination based on their gender, age, disability, and other characteristics when attempting to exercise their right to a private and family life.

While writing this article, attempts were made to retrieve public data on the rates of adoption and usage of in invitro fertilisation and surrogacy services by women with disabilities. The fact that there was no response at all from the authorities once again demonstrates the scale of the issue.

There are several steps that could be taken right now to protect and fulfil the rights of women with disabilities to a private and family life.

These include introducing disability-sensitive, accessible, and inclusive sexual education at school.

Deinstitutionalisation should take place, with the development of alternative community-based independent living services, support systems, and networks taking their place.

Modules on the rights of people with disabilities, patient rights, communication etiquette, as well as confidentiality standards should be made a mandatory and indivisible part of medical education, both at university and as a lifelong learning component.

Until these and other steps are taken, many women with disabilities in Georgia will continue to be deprived of the right to a private and family life that most in society take for granted.